Looming over Colerain Township is Mount Rumpke, the highest point in Hamilton County, Ohio. Visitors are taken by bus to the top, and from the summit, you can see the valley below, stretching to the reaches of the mountain’s domain. The skyline of nearby Cincinnati sits hazily in the distance. Far below, bulldozers and dump trucks, the size of ants, can be seen developing more mountains just like it. Mount Rumpke, with its sweeping valley and majestic panoramas, is a mountain made of garbage.

Mount Rumpke represents approximately fifteen years’ worth of trash, a mix of municipal solid waste and construction debris collected from most jurisdictions within 60 miles of Cincinnati. The Rumpke Company operates the premier garbage collection network in southwestern Ohio. Mount Rumpke sits on the company’s 1000-acre property, the accumulated garbage rising 1,064 feet above sea level, ten feet shy of its legal limit. Much of the verdant valley is actually garbage, piled hundreds of feet deep but covered over with dirt, grass, and shrubs. The landfill, like most in the USA, is licensed by the EPA, who says it can take in up to 10,000 tons of garbage per day. The Rumpke landfill is the sixth largest in the country.

That much garbage in one place makes for a landscape unique in its composition. The concentration of man-made goods, harsh chemicals, and organic waste all rotting together makes for an environment that doesn’t — and can’t — exist anywhere in the natural world. It is alien in its harshness, and yet the landfill is teeming with life. A landfill provides abundant food and shelter that gives rise to its own ecology. Landfills, while ostensibly inhospitable, have become a biological niche, a biome based around humanity’s waste.

The guts of the average landfill are actively decomposing thanks to tens of thousands of kinds of bacteria and fungi. The spread of bacteria is facilitated in part by insects like cockroaches and ants. Mice, voles, and other small mammals pick from the trash and nest in the landfill’s periphery, while raccoons, coyotes, and dogs — even baboons and bears in areas with such creatures — scavenge the top. Crows, starlings, and gulls flock to landfill en masse, and are in turn sometimes scavenged by fiercer birds of prey. For many creatures, the landfill is the beginning, middle, and end of life, the stage on which they act out the primordial directive to eat and reproduce.

An organism’s ability to survive and even flourish in such conditions demonstrates the remarkable dexterity of the natural world. But how do animals survive in a landfill? Are there benefits to making a home there? How does the nutritional value of items in the landfill compare with more traditional food sources? Have organisms developed a tolerance for the poisonous effluent that flows through the trash? This article takes a look at these questions, throwing the author (willingly) into the depths of a landfill to roam around the filth with its fascinating, industrious layers of life. The kingdom of garbage is an impressive one, an interdependent biologically functioning unit. In other words, a landfill is an ecosystem unto itself.

The putrescible groundwork for life — how a landfill works

Molly Broadwater, senior corporate communications coordinator at the Rumpke landfill, said the term ‘dump’ is pejorative. A dump implies a pit or a field where residents simply throw their waste, like those old-time trash piles way out in the country. Dumps typically don’t include any of the regulations or forethought that goes into the creation of the modern landfill, which is an engineering marvel. Landfills, also called tips and middens, don’t just hold trash but all the facilities needed to manage it. The Rumpke facility, for example, has a gas refinery to harvest the methane that builds up as garbage decomposes, a drainage system that funnels leachate — aka garbage juice — to a wastewater treatment plant, and space dedicated to the company’s trucks, including a garage, a workshop, and an area to wash off their tires so they don’t track waste from the landfill to the rest of the world.

Owing to the sheer amount of garbage delivered every day, a landfill has to think years in advance about where to store the unimaginable accumulation. When I visited the Rumpke landfill in April, the earthmovers seen from atop the mountain were preparing the next area on the property scheduled accept garbage. The site starts as a 13-acre, 200-foot deep pit, which isn’t expected to be full for eleven years. At the bottom is three feet of impermeable clay that acts as a natural barrier against leaks. The clay is followed by a plastic liner and then a geotextile cushion liner, which prevents the plastic liner from being torn or punctured by the layer of rock that comes next.

Trash dumping can start once these layers are in place. Garbage is trucked in and dumped in the assigned spot. Rumpke has a fleet of 400 of its own vehicles, some of whose routes include 400 stops. The trucks can hold 14 tons of garbage, or that of around 800 homes. Dozens of other trucks, private and commercial, visit the site daily. Waste haulers, construction crews, and homeowners pay by the pound to dump at the site. Big machines and bulldozers roam the piles, crushing down the trash with spiked metal tires. One of these machines can weigh up to 50 tons, and has the power to compact 1400 pounds of garbage into one cubic yard of space.

Trucks don’t dump wherever they feel like it. Trucks are directed to the “working face,” or the area where garbage is currently being dumped. Governmental regulations require that the working face be compacted and covered with a layer of dirt, partly to reduce odor and blowing trash, and partly to limit the amount of animals drawn to it. The layer or soil is around six inches deep, and is typically applied within 24 to 48 hours after the garbage is dumped. (Immediate soil coverage is often prescribed for food and plant waste.) As a result, there is more dirt but less visible garbage than one might expect in the landfill. A lot of the Rumpke facility looks simply an immense field of dirt, with patches of garbage here and there hinting at what’s below. But there are also the classic rolling hills of refuse: those surreal, grotesque piles that are repellent and fascinating in equal measure. Animals inhabit the calmer areas of the landfill while scavenging the garbage open to the world, taking advantage of the area’s bounty and the social opportunities afforded by the strange environment.

When a dumping area reaches capacity, layers of impermeable plastic are laid on top to seal it, sometimes including an odor control blanket, which uses odor-eating technology found in tennis shoes and trash bags. Broadwater, pointing out a five-acre expanse covered with such a blanket, said that a landfill is ideally a self-contained, leak-proof facility that should stay that way for decades. The leak-proof facility is then covered with a layer of rocks to prevent animals from burrowing, especially in the gas reclamation sites, which could introduce air and disrupt the process. Next comes a few feet of soil seeded with grass and other vegetation. (No trees are present, however, as mandated by state law. A toppled tree could rupture the top liner.) A finished, capped landfill looks at first glance like a park. The whole idea is that a landfill be “invisible at the property line,” disguising the garbage and minimizing its odor by burying it, and by employing a property-wide network of misters that vape out a vegetable-based perfume. And voila! The makings of the average landfill.

(The article that follows uses these kinds of tightly-regulated landfills as the basis for the landfills discussed herein. Many areas do not have infrastructure in place to construct landfills of this magnitude and relative self-containment. The unregulated landfills that exist elsewhere in the world (and which would certainly meet Broadwater’s definition of a dump) are vastly more open and dangerous, to organisms both inside and out. There you have a true sea of garbage. More animals would likely be drawn to these sites due to their openness, and so the populations and distribution would be a little different than what is described below. However, the basic processes of bacterial decomposition and foraging behaviors, for example, are similar enough to paint a general picture of the relationships between organisms that inhabit a landfill.)

The Rumpke family has called the Colerain Township landfill home since 1946, as has the extended family of countless organisms that likewise reside there. Just as old William F. Rumpke seized an opportunity to collect garbage where nobody yet had a monopoly[1], the creatures in a landfill are able to exploit its resources for their own livelihood. A society has been established in the landfill in deference to the natural order, and to the natural course of life.

Into the microbial depths (of garbage)

The odor of a landfill is a distinct indicator of the presence of the bacteria and fungi within it, as my aunt and uncle came to understand very well. A few years ago, they bought a house less than two miles from a major landfill. Either they were not aware of its location or were not told, but when the weather got warm, the gnarly odor of the dump came rolling down the surrounding hills and permeated their neighborhood. While the smell smelled partly like garbage, a very distinct component of the stench was sulfur, a compound present in the gas produced as garbage decomposes. The smallest layer of life in a landfill — a “robust set” of microscopic bacteria, fungus, yeast, and protozoa — consumes and digests organic materials in garbage, breaking it down like an enormous compost pile and producing huge amounts of methane gas as a byproduct of their activities.

An estimated 10,000 species of bacteria and fungi live in a gram of soil. Approximately 25,000 aerobic bacteria laid end to end would measure an inch. Bacteria, like pretty much any organism that wants to operate at optimum efficiency and comfort, are pretty picky about the conditions in which they live. Bacteria and fungi cannot grow if the temperature is too low, and they need waste with sufficient nitrogen content to make the proteins that allow them to grow. Fortunately, landfills are often porous enough to allow for the dispersion of rainwater and leachate. Leachate, shown to have a “unique geochemical composition” of highly toxic compounds[2], also contains high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen, which are crucial to bacterial growth.

A host of other microscopic organisms like nematodes, protozoa, and archea feed on bacteria and fungi, and process the organic components of garbage into a product more nutritious and easily digestible by other creatures. Nematodes contribute greatly to the decomposition of organic material because of high food consumption and nutrient recycling rates. The microscopic nematodes — numbering at 106 individuals per square meter — are also known as roundworms and make up an estimated 80 percent of all of the animals on Earth, and live in almost every possible climate and location. Scientists estimate that there may be up to one million species of nematodes, while a full half of the known species are parasitic. Protozoa are single-celled organisms that are capable of propelling themselves around and feeding, while archea are microscopic organisms that exists as single-celled beings or clusters. The landfill is not an unusual environment for archea, as they are “extremophiles,” the creatures one often hears about living in deep sea vents, gorging on volcanic sulfur, or in areas with extreme salinity or extreme heat.

But it is the bacteria and fungi that are the most crucial decomposers. Imagine a pile of garbage cross-sectioned from top to bottom. The cross-section would show layers of garbage in different stages of decomposition, with different kinds of bacteria responsible for each phase. The first stage of decomposition involves aerobic bacteria, or bacteria that need oxygen to survive. They consume oxygen as they consume organic waste, effectively melting it on a cellular level. When the oxygen is depleted, anaerobic bacteria pick up the decomposition process, as they do not need oxygen to function. They get to work digesting the compounds created by the first bacterial phalanx. These are digested into acids and alcohols, making the landfill highly acidic. Nutrients dissolve as the acids mix with any moisture present, and are dispersed throughout the landfill.

The landfill becomes a more neutral environment as other anaerobic bacteria eat the acids they’ve created, allowing methane-producing bacteria to prosper. These bacteria produce methane as a waste product of the items they are digesting. Once methanogenic bacteria establish themselves, they steadily produce gas for at least 20 years, and sometimes even as long as 50. Generally, the composition of the gas produced by these organisms is 45-60 percent methane and 40–60 percent carbon dioxide. Other gasses, such as ammonia and oxygen, are present in small amounts. Weird little capped pipes come out of the ground near active garbage sites and in the otherwise nondescript grass hills and fields. These are vents that help outgas the methane. Most of the gas, however, is harvested and processed by the on-site refinery, or burned off via flares. (Towers with what appear to be everlasting flames are a common site at landfills.) The gas is sold to energy companies, and garbage gas is even used to power some of the Rumpke’s trucks. Methane is only about half as efficient as natural gas, but according to Rumpke, who has over 200 gas wells on the Colerain property, the landfill produces enough methane to power 25,000 area homes.

Aside from the pungent aroma of decomposing garbage, landfills are stinky because of sulfides present in the gas, which are produced by anaerobic bacteria. Comprising only around one percent of its volume, sulfides are nonetheless responsible for the garbage gas’s rotten-egg odor, which is why driving by a landfill often smells like weird gas instead of trash. All of the other gasses present are odorless and tasteless; the tiny percentage of sulfides is responsible for the smell that induced my aunt and uncle to move, and for the slap they likely delivered to their real estate agent for not telling them their house was near the county tip. Though in reality, they kind of lucked out it wasn’t worse — anaerobic bacteria also produce cadaverine and putrescine, which smell exactly as their names suggest.

The establishment of bacteria in the first place depends on the contents of the landfill. Organic waste is crucial to the process, introducing bacteria into the dump as well as nutrients like magnesium, calcium, and potassium, which help bacteria flourish[3]. Organic waste is abundant in the average landfill. According to industry figures, approximately half of the landfill’s contents are some kind of organic waste — restaurant food scraps, wood and paper, textiles, etc. According to one author, “fungi and bacteria are not restricted to decomposing leaves and other plant materials. They will decompose any dead organic matter, whether it is a cardboard box, paint, glue, pair of jeans, a leather jacket or jet fuel…made from petroleum, which is made of decomposed microscopic creatures from the oceans of the Mesozoic Era.” Bacteria and fungi are also introduced into the landfill via the soil dumped on the garbage at the end of every day.

Revoltingly, industry figures show that soiled diapers make up four percent of any landfill’s intake, providing their own pungent breeding ground for bacteria. (Remember, Rumpke takes in 6000 tons of garbage per day — four percent of 6000 tons is 240 tons of dirty diapers — every fuckin’ day!) Moreover, landfills are generally able to accept carcasses and other animal waste from slaughter plants. Thus, while not common, it wouldn’t be impossible for animal remains to be mixed in with municipal solid waste, which would certainly introduce bacteria of its own. The Franklin County Sanitary Landfill, serving Columbus, Ohio and its surroundings, “will accept animal carcasses for disposal,” provided the attendant is notified and the carcasses are “disease free and in heavy bags, if possible.”[4] These remains would be dumped in the current working face of the landfill.[5] Medical waste, with its attendant bacteria, is often present as well.

The microscopic organisms create heat as they do their dirty work. Bacteria are the organisms most responsible for the entire decomposition process. They energize themselves with carbon and grow by consuming nitrogen. Their activities are powered by oxidizing organic material, and this oxidization is what causes the heat. Signs of biological activity are temperatures between 90 and 150 degrees — high temperatures facilitate the breakdown of proteins and complex carbohydrates like cellulose, the most abundant compound in modern refuse. Bacteria can withstand the surprisingly high temperatures reached by composting garbage. In fact, thermus bacteria has been found in decomposing waste: thermus has also been found in hot springs in Yellowstone National Park and deep sea thermal vents.

Coupled with the flammable methane gas coursing through the landfill, Broadwater said that one area of the Rumpke landfill was decomposing at such high temperatures that a massive fire broke out and burned for at least a week. This is roughly equivalent to your compost pile churning with such vigor that it spontaneously bursts into flames. Rumpke was unable to figure out why this area was decomposing at an elevated temperature, and the section continues to be mysteriously hot to this day. Coupled with the presence of the methane, the combustible garbage is a strange hazard to all denizens of the dump.

Worms, Roaches, “Filth Flies” and other insects

Insects are important to the decomposition of garbage because they eat a lot of trash and tunnel their way through it, which mixes and aerates it. They tear up material into smaller pieces, which is readily eaten by microorganisms. Bacteria often digest their feces. Insects are of course also food for other insects and larger creatures. Rove beetles feed on the maggots of flies, for example, while centipedes often eat worms. Further afield, the garbage grasslands contain the insects one might expect in grassland — grasshoppers, crickets, butterflies.

Some insects find their way to the trash, while some are inadvertently brought to it. Infrequent collection, loose lids, and holey containers are the prime culprits when it comes to infestation from the outside. An estimated 60 percent of city garbage containers are infested with fly larvae; fruit flies can fit through openings a millimeter wide. In another interesting case of filth in reverse, cockroaches are often found in landfills, as they hitch a ride in the belongings humans have discarded. And to make matters more unpleasant, there are mosquitoes. Standing water often found in containers or used rubber tires is an ideal breeding ground.

Insects that eat wood can also carve out a niche in the landfill, given the high percentage of organic material in the dump. Microscopic organisms and termites process the wood into a product more nutritious to other wood-eating insects, such as tree borers and beetles. The presence of termites depends on the relative moisture and nutritional content of wood, which, contrary to cartoons that show termites devouring everything in their path, they are quite selective about. (Good wood is high in both.) Like cockroaches, the presence of wood-eating insects in waste sites likely stems from the introduction of wood already infested more so than independently relocating to it.

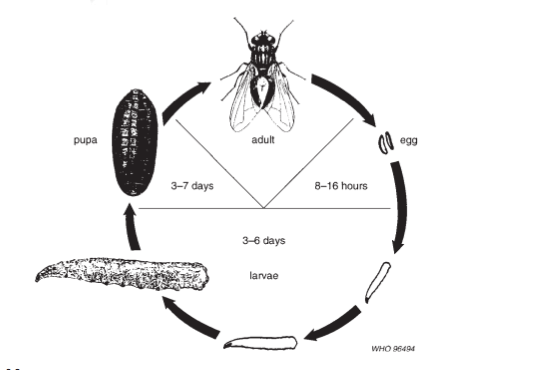

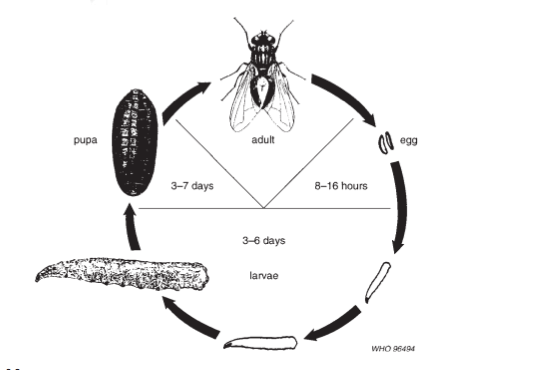

In one Calvin and Hobbes strip, Calvin relishes being a fly at a picnic table, much to the chagrin of his parents. “Filth! Pestilence! Contamination!” he says with glee (and accuracy). Flies are a ubiquitous presence in areas with any kind of decay. The whine of thousands of flies generally augurs something gross, which acres of wet, stinky trash certainly is. The common housefly is the most abundant insect in landfills around the world. Flies eat decomposing garbage, sucking up liquid waste and spitting saliva on solid items so they can be digested. Flies lay their eggs in garbage too, and are capable of reproducing up to five times over the course of their life, laying over 100 eggs each time. The emerging maggots burrow into garbage and eat it, and a few days later pupate into adult flies, where they live for a matter of weeks. Flies can also breed in cesspools and sewage sludge, environments that can probably be likened to cousins of a landfill.

As mentioned, the soil placed on top of the garbage at the end of every day is in part a pest control measure; only a serious application of soil can help reduce the amount of flies, as they need sufficient oxygen to live. However, emergent houseflies are capable of making their way to the surface through over nine inches of soil, while flesh flies and blowflies can emerge through double that. Dr. John Wenzel, an entomologist and Director of Powder Mill Nature Reserve, said that flies have a “punching bag” on their faces when they emerge from their cocoon. They use this to punch out into the world, and then head-butt their way through layers of soil and debris. Upon busting their way out of their confines, the punching bag hardens into a proper head, allowing the flies to go about their normal fly business. Flies can travel almost two miles from the trash site, and like birds and other organisms that exist in abundance at landfills, are considered pests to neighboring areas.

Also existing in abundance, to the tune of 10,000 to 100,000 individuals per square meter, are springtails, insect-seeming creatures that aren’t really insects but exist as a class of their own. Their class Entognatha includes a few other groups of creatures, though it seems almost like a catch-all for otherwise unclassifiable creatures. Some scientists maintain that the members of this group are as genetically far removed from each other as they from are insects. Their name comes from the coiled and wound apparatus that allows the insect to launch itself away when in danger. They are omnivores and microbivores that tunnel through organic material, furthering its decomposition by breaking it up and transporting nutrients and other microorganisms through the waste. Springtails are often food for other insects, like millipedes.

The hardiness of insects is in part what makes them such obnoxious pests. Insects would be more bothered by the constant disturbances of a landfill — the trucks, dumped trash, etc. — than by the potentially toxic environment of a leachate-drenched food supply, Wenzel said. Studies of gun ranges and other environments pregnant with similarly harmful heavy metals have shown that the metal-loding of lead-infused soils didn’t seem to have any effect on the insects’ day-to-day life. However, flies can pick up PCBs in the landfill and transmit them to other parts of the environment. While the environment wouldn’t necessarily be toxic to the entomofauna themselves, they could be to other animals that eat insects romping around in what is essentially toxic waste.

Living in garbage has been shown to have some odd behavioral effects. I’m not one to question anyone (or anything’s) sexual proclivities, but thanks to the ubiquity of garbage, a strange romance developed between a species of beetles and beer bottles. The Australian jewel beetle finds mates by feeling for small bumps on their paramour’s rear-end. The bumps on a certain beer bottle were so similar to what the beetles were looking for that they began trying to mate with bottles. Fortunately, however, once this phenomenon was discovered and its implications for species survival were realized, the beer company changed the design of the bottles, and the jewel beetle went back to feeling the bumps of other beetles, not something man-made.

Loafing, foraging, socially interacting: Birds

Kestrels, sandpipers, killdeer, and doves flutter and glide majestically overtop the acres of landfill — those are some of the bird species that call the Rumpke grasslands home. Birdsong mixes with the rattle and hum of machinery to create a cyborg symphony that represents the in/organic mix that is the landfill itself. The small rodents and reptiles that live in the garbage grasslands make for a good meal, and the landfill itself provides abundant resources for creatures to consume. Kestrels, the continent’s smallest falcon, can see ultraviolent light, which means it can see things like the urine trails left by small mammals, which live in abundance on a landfill’s grounds. Kestrels hide their prey in small cavities like grass clumps, bushes, or crevices in man-made structures, which likewise exist in abundance on landfill properties.

Birds flock to the landfill to eat and socialize with their brethren. Their acute senses and fearlessness allow them to eat as the humans and machines work, excavating waste not buried deep enough. A landfill in Virginia reported that it attracted 25,000 birds per day, and its daily take was only 900 tons of garbage (vs. Rumpke’s 6,000). “Loafing or social interacting” among herring gulls nesting near landfills near the Great Lakes was found to be the most prevalent activity in areas other than exposed refuse, though “aggression” was common too. Foraging was (understandably) the most frequent activity in areas with open garbage.

Landfills can provide a stable and food source for birds. As we’ve seen, organic waste makes up approximately half of the midden’s contents. One study found that a landfill in Vancouver might have contributed to the survival of bald eagle populations over winter (or at least sustaining more eagles than could normally be expected) due to the food available in the landfill. The study noted that the overall number of eagles peaked during rough weather because the landfill is protected from the wind, is slightly warmer thanks to decomposing garbage, and has fairly minimal human activity.

But the victuals in a landfill are significantly less nutritious than the food that a bird might naturally consume. Food from a landfill is literally junk food. The trade-off is its convenience, but this also means any other creature feasting on a landfill has to consume more to get the nutrition they require. This is especially true for birds, whose energy expenditures require a relatively high food consumption per unit weight. Needing to eat more means more time in the landfill, which means more exposure to predators and dangers like machinery. And more activity overall means a greater expenditure of energy, which necessitates more nutritious food. Foraging at landfills can also significantly affect birds’ health and reproduction, considering the likelihood that birds will consume non-food items or items and contamination by toxins. Sadly, young birds have often been found starved to death in landfills, with stomachs full of plastic and other inedible/indigestible items. Eagles have died after eating euthanized animals that were improperly wrapped at landfills on Vancouver Island. Dozens of Glaucous-winged gulls died after ingesting chocolate at another landfill in Vancouver.

To get a more detailed understanding of the role the landfill played in the dietary habits of the birds that flocked there, researchers collected food remains and food pellets from colonies of herring gulls. They also took samples of the stomach contents (boli) of the gull chicks. “If a chick did not regurgitate upon capture,” the study says, “we inserted a finger into its proventriculus and removed the contents.”[6] The authors found that fish was the most common food during incubation and chick-rearing, likely because it is significantly more nutritious. Adult herring gulls that specialized on garbage fledged fewer chicks than did adults that specialized on other foods. After fledging, the gulls were shown to eat more garbage, when their bodies are better able to maximize nutrients.

Eagles are primarily avivores, and the researchers who conducted another study expected that eagles would feed primarily on the gulls at the landfill. Ultimately, almost all of what the eagles ate was household food waste, and in particular red meat waste and bones. “Although some meat was identifiable, most was identifiable and clearly putrid or decomposing,” researchers wrote. Garbage made up 6.6 percent of the eagles diet, including paper towels and plastic bags. Overall, landfill refuse accounted for only around ten percent of the energy intake of the eagles that frequented the landfill. Younger eagles were apparently the refuse specialists, likely because younger eagles are less efficient hunters than adults. Eagles were also able to snatch food from other unwitting birds feeding at the site.

Despite their questionable offerings, landfills are so convenient to feeding that they’ve disrupted migratory patterns. Researchers observed white storks staying in landfills year-round in Portugal and Spain instead of their annual winter migration to Africa. The storks began staying in dumps the 1980s, in an area where they had never been seen before. The number of storks wintering in the landfills increased from around 1,200 to 14,000 between 1995 and 2015. Over several years, Birds were fitted with GPS devices, which revealed that the storks were eating, breeding, and permanently living in the landfill, as well as guarding “desirable locations” in the landfills. “We think these landfill sites facilitated the storks staying in their breeding sites all year because they now have a fantastic, reliable food source all year round,” said one researcher, though the impact of dwindling amounts of birds on the ecosystems they abandoned is yet to be seen.

Overall, bird populations are more closely controlled than those of other creatures living on the landfill. Birds at landfills are considered especially irritating to landfill managers and the surrounding homes and businesses, as well as a cause of concern to nearby airports. “The county abandoned recreational ballfields at the landfill to avoid the excessive bird droppings, and paint on nearby vehicles and buildings were damaged by the steady rain of fecal material,” reported one study. As such, one of a landfill’s pest-control directives is to reduce the amount of birds on site. Rumpke contracts with a US Department of Agriculture wildlife specialist that focuses on monitoring the bird population.

Mammalian abundance

Confession time: when I visited the Rumpke landfill and stared out at its considerable acreage, I envisioned animals living within the garbage itself — a civilization burrowing through alien waste, living in a maze of tunnels running through the picturesque mountains of trash. I pictured a community not unlike something from The Borrowers, in which insect and animals take what they need and return home to a burrow tastefully decorated with scavenged ephemera. Unfortunately (for the purposes of my own imagination at least), the reality of creatures in a landfill is not quite like this. Aside from the thriving microbial community, not much can live in the bowels of a trash mountain because its insides largely devoid of oxygen. The garbage is so compacted that it lacks significant “void space” where oxygen could collect, while most oxygen that does remain is converted to methane gas by the microbial process described above. “There’s no air there,” said Dr. Jean Bogren, a emeritus research professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago. “There’s no advantage to living in garbage.” My trash burrow fantasy realm was cruelly compacted by reality.

But this isn’t to say that animals aren’t attracted to garbage, they may just not live directly in the piles. Many mammals inhabiting the Rumpke’s property prefer to reside in the grassy areas surrounding landfills. Studies have shown that the areas around landfills are typically populated by various species of mice, voles, shrews[7], rats, chipmunks, and possums. Skunks and foxes are also present, as are feral cats and dogs. Raccoons are sometimes brought to the landfill when dumpsters are dumped in the back of garbage trucks. Omnivorous species generally fare better in dumps, as opposed to strictly carnivorous or herbivorous species, whose specific diets don’t allow them to take full advantage of the smorgasbord.[8] The most populous mammal tends to be the white-footed mouse.

Some mammals travel to and from the landfill for food and supplies. White-footed mice, for example, have a range of over 1000 feet, while woodland voles have a 600 foot range. One study observed that mice made nests made of shredded paper and leaves in bottles, cans, and other containers from the dump.[9] Burrows on the peripheries of a landfill tended to be deep enough — from 10 to 36 cm deep — to provide cover from owls and hawks, which are their main predators. Predation by raptors and other animals discourages daytime feeding or foraging. The greenspace created on covered landfills features the predator-prey relationships one can assume. It is a grassland-like environment that often draws animals such as coyotes, foxes, and snakes that prey on other mammals. One landfill worker even reported that sometimes they’ll shoot and eat a deer or turkey that wanders onto the grassland.

Landfills have been shown to attract grizzlies, baboons, and other upper echelon predators in areas where these creatures have become habituated to landfill use. Bears have been reported in landfills in Alaska and New York, and have even fed while trucks dump their haul. Grizzlies are capable of digging seven feet deep, and have excavated buried livestock. In one strange case, the fallout from eating garbage inadvertently helped temper the temper of a baboon troop. Baboons were dining on the scraps thrown in the bushes outside of a tourist lodge in Kenya and contracted tuberculosis from spoiled meat. These baboons were the alpha-male type who previously wouldn’t let anyone else get close to the meat. Incredibly, and this speaks for the innate benefits of the “can’t we all just get along” sentiment, when these baboons died from contracting tuberculosis, they weren’t replaced by the next-most aggressive males. The rest of the troop realized they didn’t have to fight for food, and were able to live communally and happily, replacing gestures of aggression with ones of affection, and having no problem welcoming new members into the fold.

Mammals, like birds, have to weigh the options of eating at a dump. Rats, for example, a frequent resident of landfills, need to eat around 35% of their body weight per day. Do they go for overall less nutritionally sound meals from the midden, or do they expend more energy travelling further for healthier meals? Does the convenience of ready food outweigh the presence of animals that would happily eat them? What about the danger posed by the garbage itself?

While the threat of a hungry coyote or possessive baboon is serious, the toxic composition of a landfill poses a grave threat to any creature that trudges through it. Leachate, that noxious juice that flows like lifeblood throughout the entirety of the landfill, is no less harmful to animals than it is to humans. Studies show exactly what happens when animals are exposed to it: an increase in cancerous legions and organ failure.[10]

In a typically cruel study, rats were injected for thirty days with different concentrations of a leachate concoction, comprised of leachate from twenty leachate wells in Nigeria. Within 24 hours of exposure, the rats showed discolored skin, un-groomed hair, and had difficulty breathing. During the second and third weeks, the rats were sluggish and ate less. Frequent sneezing, hair loss, and diarrhea occurred throughout the fourth week of the study. One rat had its eyeball bulge out of the socket, while others developed abscesses. Three rats died from the exposure during the tests, and another died a day after the tests were stopped. The pollution likely causes “direct chemical disruption of the organs.”

The study concluded that livers and kidneys are the organs most prominently affected by landfill pollution. Increased organ weight as body weight decreases, which the mice demonstrated, is a sign of toxicity, reflecting attempts to “sequester” these contaminants. Mice taken from landfills in Spain were shown to have heavier kidneys than mice from non-landfill sites, indicating their bodies’ attempts to flush out the accumulated toxins. Overall, kidneys fare a little better than most organs, reaching a “degree of tolerance or adaptation” to harsh substances, thanks to the kidneys’ deft detoxification process. Juvenile mice had elements such as lead in greater abundance, owing to higher energy requirements and the greater consumption of food this necessitates. Interestingly, shrews from the same landfills did not show an increase in some elements, highlighting differences in reaction to these elements in different species. Overall, carnivores are usually more exposed to metals and therefore accumulate more of these elements than omnivores and herbivores.

But perhaps the most pathos-inducing danger to mammals in a landfill is being accidently injured or trapped in the garbage. One Florida veterinarian and wildlife rehabilitator described “skunks with yogurt containers stuck on their heads…Plastic items become intestinal blockages; baited fishing lines entangle limbs, hindering movement and causing dismemberment; and aluminum cans with leftover soda or beer turn into razor-sharp traps.” The most heartbreaking injury was a raccoon whose paws were stuck in beer cans. “The cans had been on his limbs for so long that he had tried to learn to walk with them, and both front limbs were completely damaged,” she said. She sedated the raccoon and took the cans off of his hands, which had no fur and no skin on them.

Humans, too, have been thrust into the ecosystem of a landfill. Economic and political conditions have pushed an estimated 15 million people into this strange new world. Many landfills in developing countries offer a form of refuge and employment, allowing people support themselves and their families by scavenging useful items. In some cases, selling plastics and metals to recycling companies, for example, can provide some semblance of income. Tens of thousands of people live inside individual landfills. Communities in landfills in countries such as Indonesia, Guatemala, Russia, and Senegal have their own schools, neighborhoods, and societies.

Living in landfills, humans have taken their customary place at the top of the ecological hierarchy, but this is obviously a pyrrhic victory. Humans are subject to the same diseases, toxins, and dangers that afflict any creature that searches its way through a dump. Birth defects, tuberculosis, tapeworm, malnutrition, and fatal garbage landslides are a few of the many ubiquitous concerns. One man, who lives and works in a landfill in India, said that, due to the stench, he didn’t eat for over a week when he arrived, and vomited every day. But for better or worse, he has slowly become acclimated to life there, just as one might take to living in an unfamiliar area out of necessity. There are dangers inherent in any ecosystem, and hazards that creatures of every variety take into consideration. It’s all part of the game of life, and as we’ve seen above, millions of organisms are making it work for them.

What does this all mean?

Humanity’s current landfill practices are likely rooted in the path of our evolution. Humans were semi-arboreal as they evolved further from primates, and then finally walked away from trees. In the process, they were able to leave garbage behind and not have to think about it. Since then, garbage has, of course, been a chronic problem throughout civilization. The Middle Ages were famously mired in the excreta running through the streets, barrels of toxic waste currently impregnate mountains, and studies have shown that certain serious diseases often afflict people who live and work near a landfill. (Even the question of what to do with our own remains is also problematic. At one point, Paris had to relocate a million buried skeletons because they were leaching arsenic into the water.) Natural areas and habitats near landfills have been disrupted by the facilities’ expansion, or are at least nominally relocated. “For example, at our Brown County, Ohio, landfill,” Broadwater wrote in an email, “We built a 4-acre highly engineered wetlands to offset the destruction of smaller wetlands when we expanded the site. This wetland now houses many of the native species of plants and animals that call Brown County home.”

An appreciation for the dangers of the trash problem has become a more present part of the common consciousness. There were almost 8000 dumps in existence 30 years ago, but governments began consolidating dumps into much more regulated super-dumps in an effort to more tightly control the collection of trash and curtail its attendant hazards. There are currently around 2000 landfills in the United States. We still operate with the same sort of “out of sight, out of mind” sense of comfort that at least the trash is going somewhere, but officially, at least, we are legally bound to care about that somewhere for 30 years. Federal law requires that landfill owners have to set aside money to close the landfill and to care for the grounds for the succeeding three decades, during which they also are required to “pump the leachate, test the groundwater, inspect the cap, repair any erosion, fill low areas due to settlement, maintain vegetation and prevent trees from growing.” And in the US, opening a new landfill is a tightly controlled process involving a panoply of federal, state, and local agencies, and the undertaking of numerous impact studies. Rumpke staff said that in some cases it has taken over seven years to even get the permits that would allow them to even begin thinking about opening a new landfill. But despite the increasingly regulated process and the greater understanding of the dangers of excess garbage, our trash and what to do with it is a problematic phenomenon that is only growing. Rumpke, will its 300 acres of landfill, is eleven years away from capacity. The company is currently suing the surrounding township to expand its operations, but that will only facilitate more collection, not address the creation of so much garbage in the first place.

The average person in a developed country is responsible for generating about 2.6 pounds of garbage a day. Every three months, the average American man produces his weight in garbage. Researchers found that people threw away 289 million tons of municipal solid waste in 2012, a figure more than twice the 135 million tons that the EPA estimated for the same year, and a figure that is close to one ton per person per year in the US. By the year 2025, 4.3 billion urban residents are projected to generate approximately 6.1 million metric tons per day. Scientists estimate that 11 million tons of garbage will be produced daily by 2100. And the industriousness of the microbial process in a landfill is no laughing matter. Thanks to the methane produced by decomposition, garbage is an even faster growing pollutant than greenhouse gases. The EPA showed that greenhouse gas emitted by landfills that traps heat in the atmosphere 25 times more effectively than does carbon dioxide.

Well into the last century, New York City simply dumped all of its garbage straight into the ocean .One study found that plastics currently pollute no less than 88 percent of the world’s ocean surface. There are five major concentrations of plastic in the world’s oceans, with the largest, the infamous Great Garbage Patch of the Pacific Ocean, estimated to be twice the size of Texas. Trash is apparently even colonizing terrestrial space – there are currently almost 18,000 manmade objects orbiting Earth, with no doubt more on the way as the human races breaks free of its terran confines.

The animals at landfills currently have a tentative relationship to landfills, in that they are able to choose landfills when it is advantageous or convenient. They are still affected by the toxicity of its contents, and can’t quite establish a home in which they are as comfortable as they would be in their natural habitats. But as the amount of garbage grows and we develop new places to stash it, making a home in landfilled areas will become less of an option and more a species survival imperative. The growing patches of trash in the ocean and garbage biomes on land and the trash belt orbiting the planet will become the new frontiers of life, maybe even altering the course of evolution. Maybe ever-growing landfills will force rat’s kidneys to better accommodate heavy metal loding, or will help birds derive maximum nutritional value from the pickings they scavenge. Perhaps beetles will be able to consume Styrofoam, or maybe skunks will develop a coat of such incredible density that chemicals can’t penetrate it, or creatures will be able to nest in a mound of diapers. Claws will become refined to dig through piles of old appliances, proboscises will puncture through old batteries, and eyesight will evolve to see around the corners of old couches. Maybe new creatures entirely will develop, boasting an agglomeration of appendages especially suited for living in a landfill. Maybe new forms of bacteria will spring up that can metabolize circuit boards, bridging the gap between carbon-based life forms and virtual intelligence.

These changes will happen at evolution’s grindingly slow pace, but by the time these creatures have adapted to life in vast ecosystems of garbage, future researchers will marvel at how readily and how ingeniously these creatures have adapted, and continue to adapt, to their befouled environs. Studying the creatures from generations ago, marveling at its ability to survive in the mire before their specialized adaptations, the researchers will perhaps look out their window and gaze out at the world in awe at the workings of nature, their musings accompanied by birds mimicking the chime of enormous trash-crushing machines. High up in a building built among reclaimed trash piles, looking over the trash mountain range and the lovers paddling canoes down leachate rivers, a scientist smiles, pushing his triclops glasses up a nose evolved to selectively filter smells.

“Our world is a landfill,” he says. “A fascinating ecosystem unto itself!”

Notes:

[1] The Rumpke landfill started as junkyard and coal delivery business sometime in the 1930s. A customer traded founder William F. Rumpke six pigs for his services, and he refurbished an old truck to bring garbage back to feed the pigs. Rumpke established a facility to take in metal during World War II. People would bring their trash to his property, where it would be dropped on a conveyor belt and sorted by hand. Metal and rags were set aside for the war effort, while the rest remained trash. In the 1950s, the government passed a law mandating that food waste be cooked before it was fed to animals. Finding this too inefficient, Rumpke, who by this time was joined in business by his brother, sold his animals and concentrated on trash. The business grew and grew, and in the 1980s, the company consolidated area trash services by buying over 200 businesses and established outposts of their trash empire all across Ohio and surrounding states. In 1986, Rumpke started harvesting methane gas from its landfills (one of the first such operations in the country), and in 1987, Rumpke purchased a portable toilet business. Rumpke also runs a massive recycling facility (which truly has to be seen – and heard – to be believed) and other related businesses. Rumpke currently employs almost 2500 people, 75 of which are Rumpke family members.

[2] Such as toluene, phenols, benzene, ammonia, dioxins, PCBs, and pesticides.

[3] Dry conditions and high salt concentrations, however, can curtail bacterial growth, as can low nitrogen content and high carbon dioxide content in soil pores.

[4] These remains would be dumped in the current working face of the landfill, as opposed to the elephant that’s buried on the Rumpke site. An elephant that died when a circus passed through town is buried on site, but not near the garbage. Also buried at the Rumpke landfill are the world’s largest chocolate bar and “Touchdown Jesus,” an enormous fiberglass Jesus that faced the highway from the lawn of a church. The figure’s arms were raised in the air, affecting a gesture very similar to that which referees use to declare a touchdown. The statue was struck by lightning, caught on fire, and melted. Rumpke accepted the remains. The church has since rebuilt the statue, this time out of cement.

[5] I can attest to this: once, when I worked for a construction crew, I accompanied my boss to dump our trailer at the dump. We drove out to the working face and got to work preparing the trailer. It was windy, and we laughed that trash was blowing all over us. I saw that there was a lot of medical packaging blowing around. I looked down and saw that I was standing on a fairly large spread of medical waste, including syringes, catheters, and other indistinct but clearly biohazardous items.

[6] Contents were separated into categories – fish, garbage, insects, plant food – and counted. Garbage comprised roughly 11% of the boli’s contents, 17% of the food remains found near nests, and less than one percent of the content of the food pellets.

[7] Special consideration was necessary for counting the short-tailed shrew. “The method of tagging by toe clipping is less reliable than ear tagging because of the possibility of shrews losing their toes to natural causes,” noted the authors of one study.

[8] One landfill in Virginia even attempted to introduce a new mammal to its grounds: goats. But, after a year, “officials realized that using farm animals to cut grass was not the easy solution originally imagined.” The situation did not improve even when sheep were brought in to augment the finicky goats. The final solution: officials acquired two lawn mowers to cut most of the grass on the landfill. “The same city official who initiated the goat project later proposed creating a mulching operation at the landfill. Supervisors rejected the proposal, but he purchased $500,000 of equipment without approval. He resigned in 2015 just before he would have been fired.”

[9] The authors noted that their study was conducted before an outbreak of Hauntavirus, and that they were not conducting a mammal survey at the time the study was published, which was apparently during the outbreak.

[10] Similar dysfunctions of the kidney have been reported in human workers associated with the treatment of industrial waste. A study done by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine suggests a possible increase in cancers and birth defects in humans who live near landfills.